Discover more from News from Dorothy Ramon Learning Center

One day three years ago, a Riverside Community College student felt curious about Southern California’s own Native languages. So, he looked around on the Internet. He read that the Serrano language of Inland Southern California was dead. He then learned that’s fake news, because he found Dorothy Ramon Learning Center, and Center President and Elder Ernest Siva (Cahuilla-Serrano).

He asked to meet Ernest Siva. Ernest Siva made the time. The student drove from Moreno Valley and said he wanted to learn Serrano from Ernest Siva. So, they met some more.

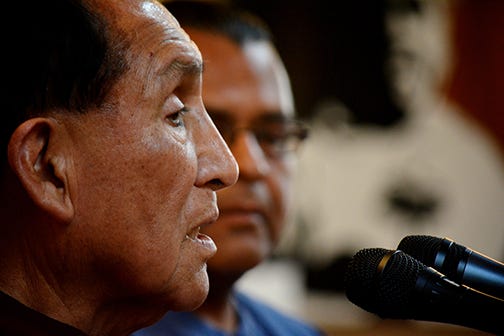

Ernest Siva at Dorothy Ramon Learning Center’s 2015 Native Voices Poetry Festival (Carlos Puma Photo).

Three years later, Mark Araujo-Levinson, now a mathematics student at California State University, San Bernardino, is helping Ernest Siva teach Serrano. He also has been helping with Serrano programs at Morongo Reservation School. His goal is to help revitalize or awaken Native California’s languages.

Mark Araujo-Levinson tells a story in Serrano at the 2019 Native Voices Poetry Festival (Carlos Puma Photo).

Here is his story about the Chumash language family.

A Journey to Discover Chumash Languages

by Mark Araujo-Levinson

The Challenge

In late 2018, while I was deep into my Maarrênga'twich (Serrano) studies, I looked at a map of all the tribal groups in California. While there are so many different groups that I could have looked into, I decided that I wanted to look at another group of Natives from Southern California besides what would be called the Uto-Aztecan group. I looked towards the north and the coast to a large group of people who were named the Chumash. Of course, my instinct was to go straight to Google or Wikipedia for information. Once I looked, it had said that the whole language family was "extinct" with the last speaker of a Chumash language, namely Mary Yee, who had spoken the Šmuwič (Barbareño) language. Even though some people will just forget about a "dead" language, that just makes me even more intrigued.

“The Words Sounded Like the Waves of the Oceans”

I saw that there were 6 different languages, which they called: Ventureño, Barbareño, Ineseño, Purisimeño, Obispeño, and Island Chumash/Cruzeño. So, my Google search continued for any information on any books, grammars, or literally anything to learn something about the languages. Fortunately, I was able to find a grammar done by linguist Richard Applegate on Barbareño Grammar, and also recordings done by Madison Beeler of UC Berkeley of Mary Yee. I had spent a couple of weeks trying to hear the words of Mrs. Yee, trying to get the phonology. The words sounded like the waves of the oceans of Santa Barbara, and I was being drawn into how beautiful these languages are.

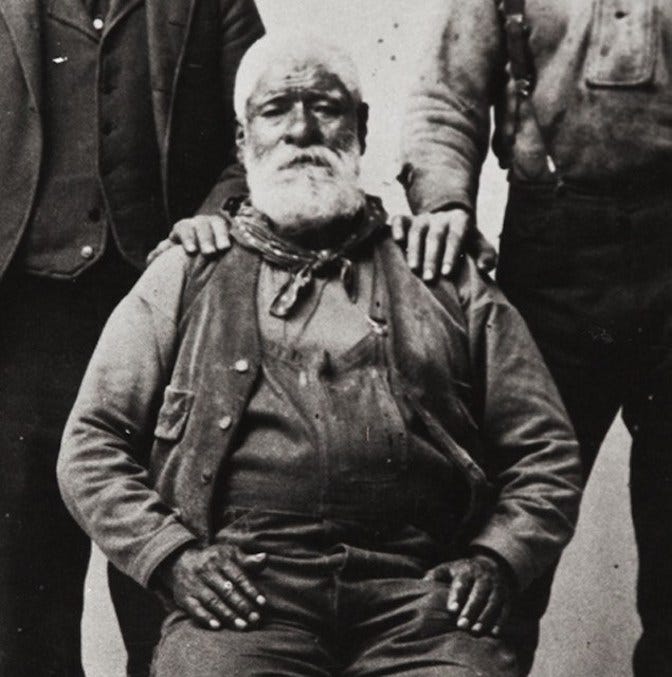

Although I was understanding bits and pieces of the grammar, it did not really stick with me. So, I decided to move in a direction which was probably not smart, but to me extremely eye-opening and rewarding. I decided to look at the Obispeño language, which was said to be the most divergent out of the whole group, which has not been spoken in over 100 years. The last known speaker of the Obispeño language was Rosario Cooper, who had passed away in 1917.

Rosario Cooper, speaker of the Obispeño Chumash language, seated at viewer's right outside her home near Arroyo Grande during her linguistic work with John P. Harrington, 1916. Left to right: Mauro Soto, Rosario's husband, J. P. Harrington, Frank Olivas, Jr., Rosario's grandson, and Rosario Cooper. (Courtesy of Calisphere)

Deciphering J.P. Harrington

For more than 40 years starting around 1915, JP Harrington collected more than one million pages of linguistic and ethnographic notes from Native Americans. (Photo courtesy of the National Archives)

Although I wanted to learn the language, I was at a dead end because I had found out that all of the information that I really wanted was in a pile of about 4,000 or more pages of field notes done by John Peabody Harrington interviewing Rosario Cooper. I had found out that the Smithsonian offers a great majority of Harrington’s field notes online. So I went to Reel 1, and I found out that I had no idea how to read his notes. Luckily I had reached out to a member of both the Ventureño and Barbareño Chumash, who was kind enough to help me read Harrington’s notes. After a couple of weeks, I was well upon my way to tackle the many pages of notes.

Cherishing Words from More than 100 Years Ago

As I delved deeper into the notes, and reading the words of a woman who was very funny and feisty, I started to feel connected not only to her, but to the language.

Phrases like “kɨnɨpł'uwawa tš'ana yapsuyu'” (“Don’t be a crybaby like your wife”) made me laugh aloud, and other phrases such as “misaqinɨłhɨ yakłhina kłtʸu, mihisini yamt'ɨnɨsmu'” (“I advise you to take the good road, use my words”) carried wisdom. As I went through the tedious task of writing down every single word and phrase that was written on the page, I began to fall more in love with each page that had gone by.

Rosario Cooper. Image originally obtained from Harrington Papers, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution 91-31284. (Courtesy of Calisphere)

Since these notes were taken over a century ago, I only wish I could hear the voices of these truly important people that I am dedicating my time to, but they are only on wax cylinders, or CDs at UC Santa Barbara where I cannot go to listen [due to the pandemic].

On January 28, 2018, while I was watching a snippet of a future documentary on John Peabody Harrington, I finally got to hear a snippet of the voice of Rosario Cooper when she was singing a Deer Song. This resulted in me in tears because there was something about working to learn her language, but never knowing what she sounded like. I had it on repeat, and I still listen to it to this day. After many weeks and months of learning what is called Tiłhini, I decided it was time to revisit the other Chumash languages because just like Harrington, I wanted to know as much as I could.

Fast forward to 2020, the whole Chumash family is a family that is very close to me. I truly enjoy learning and trying to speak them:

Just like I did in the past, I wanted to look at the other divergent member of the Chumash family, namely Cruzeño. Since I have had some experience with the other divergent member. I thought it was something that I could tackle, but this time it was not so simple. The last known speaker of Cruzeño was a man named Fernando Librado, who had passed away in 1915. He also helped Harrington with the Mitsqaniqa’n or Ventureño language. From what I have heard, Fernando Librado was born on Santa Cruz Island, and was brought to Ventura while he was really young. Reportedly, he learned Cruzeño from his parents who were native speakers, while he was becoming a native speaker of Ventureño. I am unsure if he was himself a native Cruzeño speaker, but seemed to be quite familiar with it.

Fernando Librado (Courtesy of National Park Service)

I had gone through all of Harrington’s notes on the language. The majority of it was just vocabulary terms such as: body parts, family, people, animals, etc., while very few pages were dedicated to sentences and things along those lines. That made it a bit more difficult to learn how the grammar of the language works, but again it seemed very different than the mainland languages. There was and there still are things that I truly don’t understand about the language and how it functions. I understand that there is an unpublished grammar on the language that hopefully one of these days I will get to read to fill in the gaps of the language, but until then all I can say is ‘aničxup (I don’t know). I love all of these languages, and I will continue to dedicate time to learn them, speak them, and talk to others about them.

Persevere!

Whatever language that you want to learn or you would like to know more about, go and try your best to learn it. I know that it might be easier to find books on how to speak Spanish, German, or French. You can learn any of those languages any time any day. They aren’t going away anytime soon. There are languages out there that you might not know you love. You just have to keep on looking.

Ernest Siva at Dorothy Ramon Learning Center’s 2019 Native Voices Poetry Festival (Carlos Puma Photo).

Save and Share!

We thank Mark Araujo-Levinson for sharing his personal journey with the Chumash languages with us! We are thankful to those Elders who shared the languages via wax cylinder so many years ago. Please help save and share cultural knowledge now, for future generations.

Dorothy Ramon Learning Center is a 501(c)3 nonprofit that saves and shares Southern California Native American cultures, languages, history, and traditional arts. Join us at dorothyramon.org and Dorothy Ramon Learning Center on Facebook.

We welcome your ideas and contributions to News from Dorothy Ramon Learning Center: EMAIL. Pat Murkland, Editor. Dec. 9, 2020.