By Pat Murkland

During the tumultuous 1800s, after increasing hordes of newcomers pushed Native American people from their homelands and onto reservations, where traditional food and water sources were throttled, and all traditional aspects of Native families’ lives were disrupted, Serrano political leader John Morongo told the children in his extended family that he wanted them to go to the reservation’s new school.

He told them in the Serrano language that he wanted them to learn how to read, write, and speak English, and learn the ways of these non-Native people, at the federal government’s day school.

Was John Morongo abandoning Native ways to assimilate into non-Native culture? Absolutely not, according to Elder Ernest Siva (Cahuilla-Serrano), John Morongo’s grand-nephew, and president of Dorothy Ramon Learning Center.

This was instead a strategy of resiliency, Ernest Siva says. John Morongo’s older brother, Francisco, the Serrano kika, or ceremonial leader, had already shared with the people how this chaotic time was foretold during the time of the Creation.

Ernest Siva says his great-grandfather Francisco Morongo said the prophecy had told of the coming of “younger brother,” and that the people should learn the new ways to adapt and cope with the changing world brought by younger brother. However …

Never Forget!

“At the same time, Francisco Morongo said, never forget your culture: your language, your stories, and your songs, for these are what and who you are,” Ernest Siva says. “Otherwise, he said, you will become Lost People. Your roots will be like those of shallow grass instead of those of a mighty oak.”

Day-school on the Reservation

Soon after the U.S. Indian Service teaching job opened on the (Morongo) reservation, then known as the Potrero, Sarah Morris left a school in Joplin, Missouri, where she’d been teaching eighth and ninth grades. She traveled alone by train and arrived in Banning, CA, on March 23, 1888. Her best friend Estelle Ingelow, already in the tiny town of Banning, had telegrammed her to tell her of the job opening nearby, and Estelle’s husband was waiting for Sarah Morris at the train depot.1

In Victorian times, teaching was one of the few socially acceptable tasks for the single woman. Sarah Morris was 29, nearly 30. Remember that 1800s women weren’t allowed to vote, be leaders, own property, or speak their minds outside their kitchens. A woman traveling alone about 1,500 miles by train in 1888 already was journeying away from what was expected of her.

The day after she arrived, Sarah Morris went to the reservation to start teaching. She would live and teach on the reservation as an employee of the U.S. Indian Service for the next 17 years.

The first schoolhouse was an old adobe home that belonged to John Morongo. She lived in back. On weekends she visited her friends in Banning. During the week she would visit the families of her students after school and see how she could be useful or help them. For example she shared medicines from her medicine bag. (Native people weren’t allowed to go to public hospitals in the 1800s.) Some became her lifelong friends.

Most of the first students were members of John Morongo’s extended Serrano family. John Morongo’s political rival, Cahuilla political leader and powerful puul or medicine man Will Pablo, initially held off; his successful strategy of resiliency was to be independent and sometimes be uncooperative with federal Indian agents. Later, Cahuilla children also would attend.

Sarah Morris’s first class of 20 boys and girls of different ages spoke no English. John Morongo’s daughter, Annie, served as Serrano interpreter. Note that Sarah Morris was teaching bilingual education in 1888. Her students learned English as a second language. After school each day they went home, where they continued to speak the Serrano language and practice Serrano culture with their families.

(Generations later, the 2023 Morongo School on Morongo Reservation teaches students the Serrano and Cahuilla languages and cultures.)

In this photo from Sarah Morris Gilman’s photo album, members of the first class are standing in front of the adobe building that John Morongo gave for the first school. Sarah Morris is in the doorway, in back, and Capt, John Morongo and his wife, Rose, are standing at far right, fading into the poor quality of the photo. Their daughter Annie, the Serrano interpreter, is standing just to their left in the back row. Note that both the girls and the boys are being taught. (Photo courtesy of the Huntington Library’s William H. Weinland Collection, Box 7, photCL 39 Volume 2)

From the first day, Sarah Morris fought for equal rights in education for her Native American students. Her stated goal was to teach them so they could be equal to non-Natives. A local newspaper, for example, chronicled at one point how she fought for a classroom globe so she could teach geography to the Indians.

Her strongest ally was her friend the Serrano political leader John Morongo. Neither had voting rights or acknowledged basic civil rights in 1800s America.

John Morongo named his youngest daughter Sarah, after Sarah Morris. Sarah Morongo Martin later became a tribal leader and the last Serrano ceremonial leader on Morongo. Her descendants include current Morongo tribal leaders.

The New Schoolhouse

At one point the schoolhouse moved from the broken-down adobe belonging to John Morongo to a former barn. When Sarah Morris returned from a summer vacation, “I found that a lean-to had been built adjoining the school building, a tiny room which I was to occupy,” she wrote in a local newspaper in 1938.2 “I moved in, but when the winter rains came it was found to leak almost like the proverbial sieve. After one hard rain my bed was thoroughly water-soaked during the night and I took a bad cold, and soon was too hoarse to talk. I continued to teach by giving written work, until an inspector arrived and asked me the cause of this indisposition.

“When told, he inspected the quarters I was occupying, and being a man of great volubility in swear words, he expressed himself in no uncertain terms on the subject, declaring that it was a disgrace to the government and to the Indian Service for a teacher to have to live in a place like that. Proceeding to the agency, he instructed the agent to see to it that my quarters were improved …

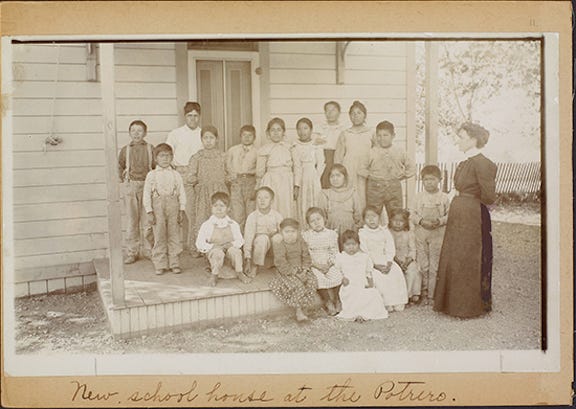

From Sarah Morris Gilman’s photo album, with her students in front of the new schoolhouse. (Photo courtesy of the Huntington Library’s William H. Weinland Collection, Box 7, photCL 39 Volume 2)

“Capt. John [Morongo] and I conceived the idea that we should have more spacious quarters. I called forth all of my nerve, and wrote to the agency, asking for it … my plans and requests met with approval, and within a brief time the superintendent came out and asked for suggestions as to a location for the new school, and within three months a well-built and nicely finished building was ready for occupancy. It was somewhat larger, painted white all through, and I felt my new home was good enough for a queen. My residence with the Indians covered a term of seventeen years and the remainder of these years was spent in this building which was comfortable and commodious for one person.”

On the steps of the new schoolhouse, which John Morongo and Sarah Morris fought for. (Photo courtesy of the Huntington Library’s William H. Weinland Collection, Box 7, photCL 39 Volume 2)

Thank you

News from Dorothy Ramon Learning Center Editor Pat Murkland thanks the California Arts Council for a Creative Corps grant enabling her to share and explore with the community the mostly untold story of Sarah Morris Gilman (1858-1941), a woman ahead of her time, who successfully championed equal rights, education, health for Native Americans, and overcame many barriers to women to also transform the local community. Read about Sarah Morris taking the Morongo students to meet the U.S. President here. Watch for more in 2023-24.

And thanks for supporting the 501c3 nonprofit Dorothy Ramon Learning Center, led by Elder Ernest Siva (Cahuilla-Serrano) following his great-grandfather Francisco Morongo’s mandate, “Never forget your culture: your language, your stories, and your songs, for these are what and who you are. Otherwise … you will become Lost People. Your roots will be like those of shallow grass instead of those of a mighty oak.”

And as always, thanks from Center leaders Ernest and June Siva and Editor Pat Murkland for enjoying News from Dorothy Ramon Learning Center, your FREE online weekly newsletter. We welcome your ideas and contributions. PLEASE EMAIL. October 27, 2023.

Based on years of research by Pat Murkland, via numerous primary and secondary resources and accounts, including Sarah Morris (later Gilman)’s own words and writings.

1938 Banning, CA, newspaper article written by Sarah Morris Gilman shared in Virgina Sisk’s self-published The San Gorgonio Rendezvous: The Smiths and the Gilmans, © 2016 Virgina Sisk, Hemet, CA, pp 115-117.