By Pat Murkland

As the U.S. Department of the Interior releases its first investigative report on the tragedies of Native American people in federal boarding schools, let’s talk about our own small local former boarding school, St. Boniface Industrial School — and its cemetery — in Banning, California.

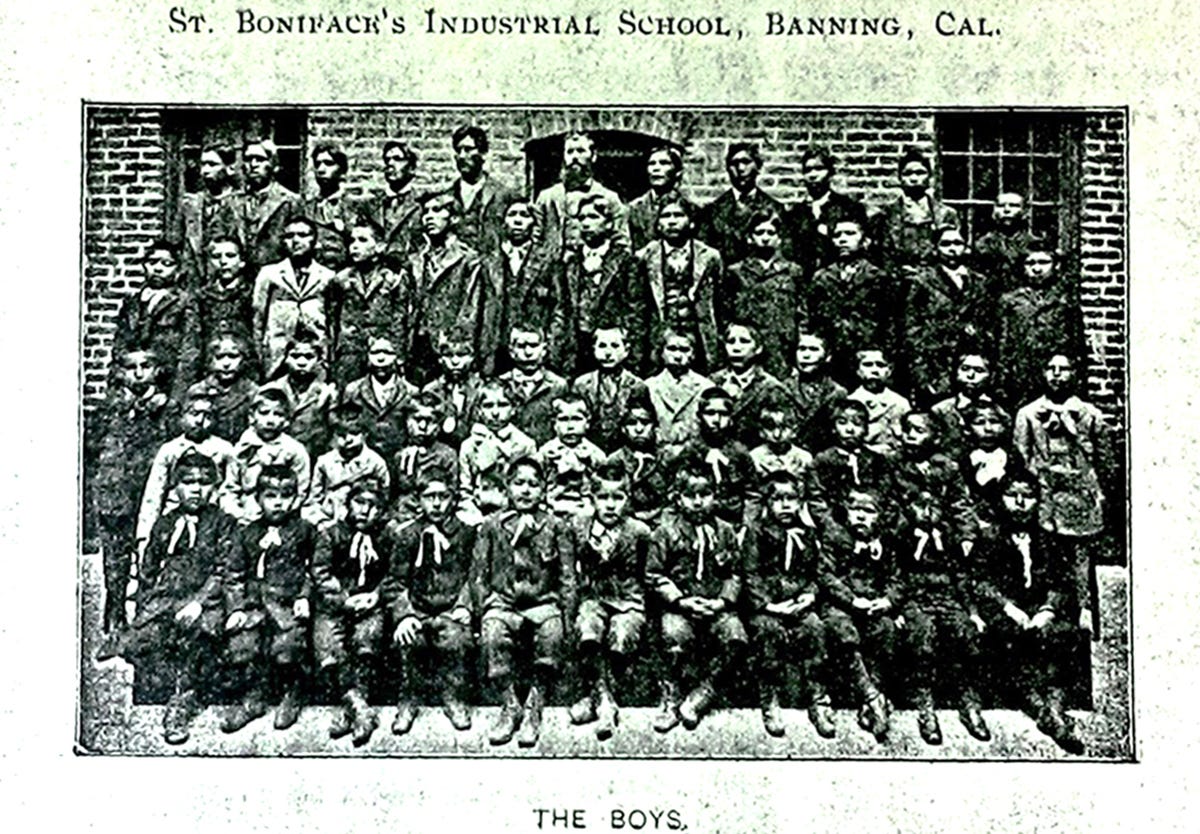

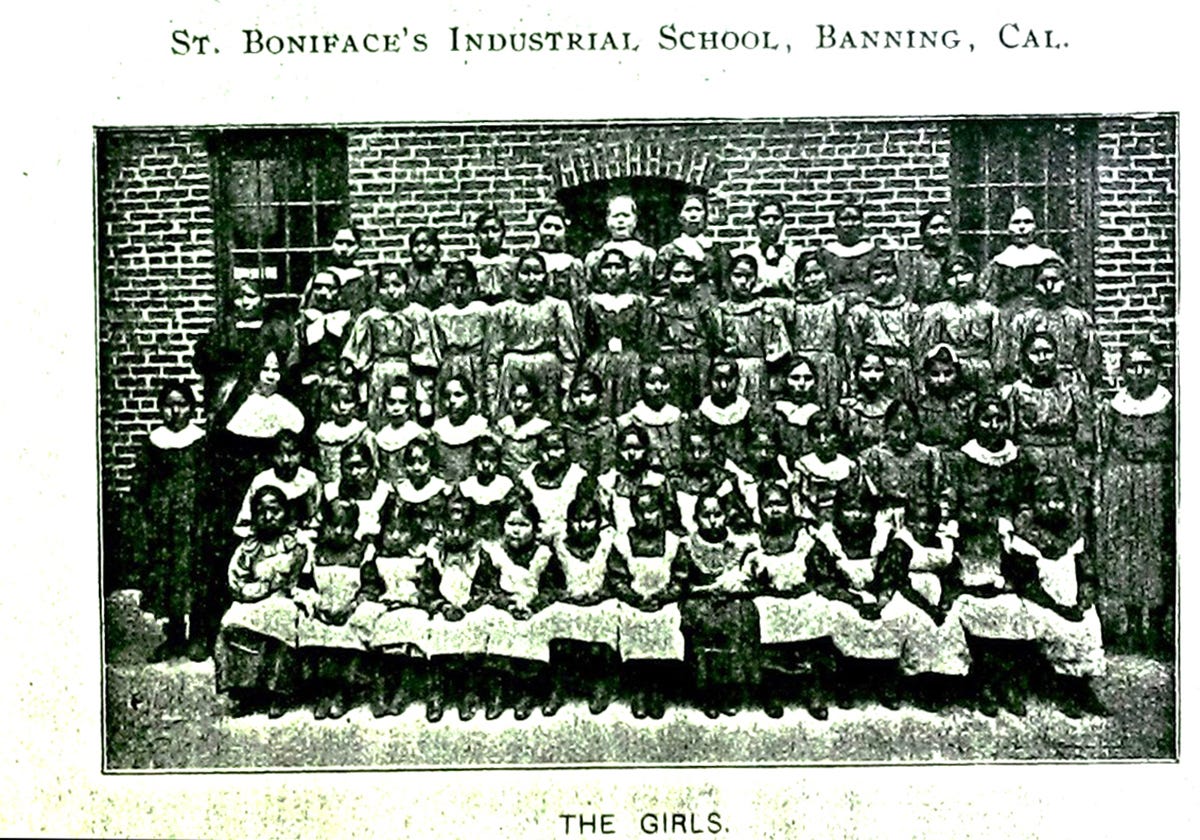

This begins a News from Dorothy Ramon Learning Center occasional series about St. Boniface. We begin with these photos from a copy of a brochure, “St. Boniface’s Industrial School for Indian Boys and Girls, printed at St. Boniface’s Industrial School, Banning, California.” Someone had handwritten on the cover, “1898.”

(Note, the same photos appear in an article in the Roman Catholic Indian Sentinel magazine 1905-1906 issue.)

No names are shared. But these photos do tell us a lot about St. Boniface.

First, the school, which focused on Native American and underprivileged children for nearly a century, wasn’t a federal boarding school. Roman Catholic Bishop Francis Mora of the Monterey-Los Angeles Diocese summed it up when he announced plans in 1888 to “build up religion in the hearts of those children of presumably Catholic people, the Mission Indians.”1

After some ups and downs in getting the money together, the Banning school opened in 1890 to carry on the work of the California Roman Catholic missions, aiming at children. From the start, the school was very much focused on the afterlife in heaven of its students — that is, their souls — with Roman Catholic religious services and liturgy dominating each day and stretching into the night. The children’s future on Earth was seen as providing blue-collar labor for the region’s growing cities, communities, and industries.

As discussed briefly in our April 13, 2022 News , and as shown by their aproned uniforms in the photos, girls spent their time on domestic work such as cleaning, sewing, and cooking. The boys worked in hard labor, carpentry, shoe-making, farming, and beekeeping. The school was “industrial,” the brochure explained, because “experience has proven that a higher education is not a success for the Indians.” 2

(Note that two years before St. Boniface opened, at the nearby Morongo Reservation government day school, Sarah Morris (later Gilman) was praised widely for her work in successfully teaching Native American children the same academic fare that non-Indian students learned, including writing, reading, mathematics, and geography.)

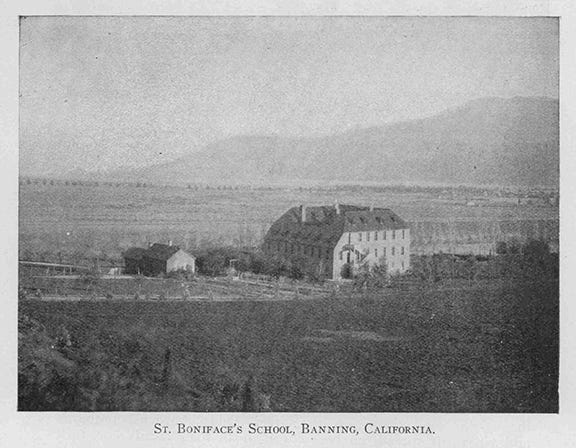

Photo of the boarding school as featured in the 1905-1906 magazine, The Indian Sentinel, published by the Society for the Preservation of the Faith among Indian Children. The Society was a fund-raising organization under the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions, which oversaw the school.

The federal government initially did fund the school, supporting tuition for 100 students at $125 each,3 with the remaining students receiving charitable donations. When government support ended after a couple years, nun and heiress Katharine Drexel of Philadelphia was one major donor who kept the school going. She also had doled out the then-huge sum of $40,000 for land and school supplies in preparation for the school’s opening.

Which brings us back to the photos of the boys and the girls. About 90 of the 120 students were described as “full-blooded” Native Americans, including Cahuilla, Serrano, Kumeyaay (described as “Diegenas”), Luiseño, and Tulare people from ages 8 or so to 18 years. Instead of learning from their Elders and family members, they were dressed in uniforms, working in the kitchen or out in the fields where, soon, 35 acres of fruit trees would be growing. For added exercise, the boys marched daily with the school disciplinarian.

Closeup of boots on boys.

And they were wearing boots. This is what caught our eye the other day when looking at these photos. Every student in the photos seems to be wearing boots. In the Victorian 1890s, both women and men wore boots for all occasions, whether listening to a performance of an opera, or riding a horse, or walking about town. But Native American children probably were barefoot, or wearing a basic sandal, if anything. Boots must have been at the very least, uncomfortable for feet used to running around without being penned in.

Boots had to be a major cultural change. Yet they were a very small part of the boarding-school attempt to remove the Native from Native Americans.

After the school opened, a local Banning shoemaker was hired to teach the boys how to make boots. But boots had to be ordered for all the school pupils, from small sizes on up. The photos also show older students who are young adults. Boots were being mass-produced by the 1890s, so there probably weren’t custom fits for 240 varying-sized feet at St. Boniface.

In the first issue in 1895 of The Mission Indian, the newspaper that the longtime school leader, the Rev. B. Florian Hahn, wrote and published with a printing press at St. Boniface, Father Hahn praised a Los Angeles shoemaker. In what probably is an 1890s version of thanking a sponsor with a social-media shoutout, the priest became an influencer.

He advised readers to order their shoes and boots at The Queen Shoe Store in Los Angeles. There, he said, one would find satisfaction, especially those needing to order from remote locations. There, he told readers, they would find “the lowest price.” 4

Thank you

Dorothy Ramon Learning Center, led by Elder Ernest Siva (Cahuilla-Serrano), saves and shares Native American cultures, languages, history, and traditional arts. We welcome your EMAIL. Thank you from Editor Pat Murkland, May 11, 2022.

R. Bruce Harley, Readings in Diocesan Heritage: St. Boniface Indian School, “Seek and ye shall find: St. Boniface Indian Industrial School, 1888-1978,” V. 8, Diocese of San Bernardino, publisher, 1994. p.1.

St. Boniface’s Industrial School for Indian Boys and Girls, booklet marked “1898,” “printed at St. Boniface’s Industrial School, Banning, California,” unnumbered page.

Bruce Harley, Readings in Diocesan Heritage: St. Boniface Indian School, p.12.

The Mission Indian, vol. 1, issue 1, Oct, 15, 1895.