Discover more from News from Dorothy Ramon Learning Center

It is with deep sadness and unending gratitude that we say goodbye to our longtime friend, and Dorothy Ramon Learning Center’s 2013 Dragonfly Award winner for soaring achievements in saving and sharing Southern California’s Native American cultures, Daniel McCarthy.

Daniel McCarthy (Photo Courtesy of Britt Wilson)

Daniel McCarthy deeply respected Native American people and their relationships with their homelands. Not long after he first became the U.S. Forest Service tribal liaison, in 1995 Daniel McCarthy organized the first Tribal Government Program workshop in Southern California in which San Bernardino National Forest staff members met with representatives of area tribal governments. They began working together to develop partnerships over traditional food gathering, reseeding of native plants, prescribed burning, and other concerns.

“I sometimes characterize my position as an ambassador for the forest representing the federal government working with tribes,” he said in 2011. “An ambassador knows the culture and customs of the nation he works with and is familiar with important issues and concerns. Protection of sensitive cultural resources and access to traditional gathering areas are two examples, of what I do.”

He said: “From a tribal perspective, I would have to say a lot of the Elders that I have been in contact with for the past 35 plus years have had a great influence on who and what I am today.” And when asked what famous people in history he’d like to have dinner with, Daniel McCarthy immediately replied: “Oh, I could think of several Cahuilla Indian Elders,” including Joe Patencio, Juan Siva, and Pedro Chino.

Ernest Siva: A Journey to Family Ancestral Lands

Rock Imagery and Desert Trails,

along with Roast Turkey, Beans, and Sourdough:

Memorial to Daniel F. McCarthy, 1948–2021

By Michael K. Lerch

Last week we lost a good friend, Daniel McCarthy, to the scourge of melanoma he had beaten two decades earlier, only to have it return. When I first met Daniel in 1978 we were anthropology students at the University of California, Riverside, where he completed his undergraduate work in 1981 and his master’s degree in 1993, with a thesis on ancient trails that radiated from McCoy Spring in the Colorado Desert region of eastern Riverside County. He grew up in Tucson, Arizona, and began his college education at the University of Arizona with a focus on forestry and watershed management.

Daniel McCarthy (Photo Courtesy of Britt Wilson)

His education was interrupted by the war in Vietnam, where he served with distinction in the U.S. Army. He was wounded in action and awarded the Purple Heart. Although he carried with him shrapnel in his leg as a painful reminder of the war for the rest of his life, he was renowned for his ability to out-hike anyone of any age, especially when it involved field trips to the mountains and deserts of southern California. Daniel rarely spoke of the circumstances that left him as a disabled veteran, yet he always supported veterans’ issues and returned twice to Vietnam and Laos to search for the remains of servicemen who were missing in action under the Joint Task Force, Full Accounting Missing-In-Action initiative. Both trips were successful in identification and recovery of MIA soldiers.

After working at Joshua Tree National Monument with the National Park Service, he returned to school and for years maintained the archaeological records archive for Riverside, Inyo, and Mono counties in the Eastern Information Center, at UC Riverside’s Archaeological Research Unit, where we both also worked as field archaeologists on a variety of projects. The first time I went to the field with Daniel was in the spring of 1979, when we surveyed and recorded the cultural resources of Indian Rock Ranch in Garner Valley. That was also the first time I was treated to his famous sourdough biscuits.

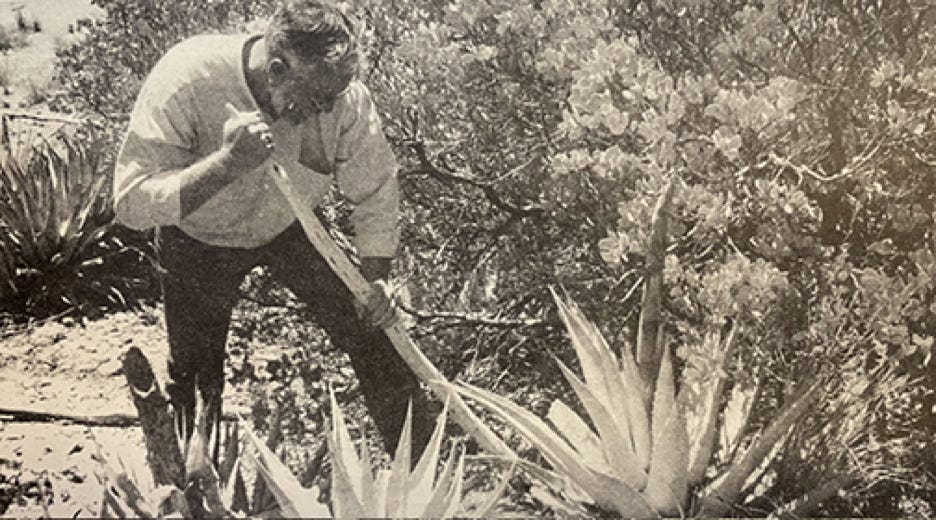

Discussing native plants at an agave harvest (Photo Courtesy of Britt Wilson).

In addition to walking Native trails in the desert, Daniel had an abiding interest in the rock imagery — pictographs and petroglyphs — found throughout the region. Early on, he developed methods to record and describe these images accurately, using mylar overlays and other techniques before modern technology allowed for even better detail. However, he never attempted to interpret the meanings of these drawings, believing that could only be done by their makers. He studied the resources and wrote technical appendixes on trails and rock art for many professional archaeological reports prepared for government agencies. Daniel was a lifelong member of the American Rock Art Research Association, one of only two members to attend every annual meeting from its founding in 1974 through its last in-person meeting in 2019. He also was interested in ethnobotany, and published a book with Malki Museum in 2009 on medicinal plants used by area tribes. He served on the board of directors at Malki for many years, and also led an annual agave harvest and roast each spring for more than two decades.

Daniel McCarthy using a traditional stick made from mountain mahogany to uproot an agave plant for the Malki Museum’s second agave harvest and roast in 1996. (Courtesy of Malki Matters newsletter, Summer 1996, p. 4)

Following his time at UC Riverside, Daniel served as Tribal Relations Program Manager and Archaeologist at San Bernardino National Forest from 1994 to 2012. During that time, he arranged for and promoted a series of archaeological field schools in collaboration with local universities and private firms beginning in 2001, which ultimately became the Applied Archaeology Field School from 2006 to 2011. Many students trained during these schools now occupy positions in federal and state agencies such as the Forest Service, Caltrans, and Cal Fire. He also contracted numerous archaeological studies on the Forest following fires and in preparation for control burns and other projects, always in collaboration with local tribes. In 2012 he was hired as the first director of the cultural resources department for the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians, where he worked until his retirement in 2018.

Those who knew Daniel well perhaps noticed the coil of string he wore around his left wrist for the past fifty years. He was taught to make string figures such as cat’s cradle by Native American elders, and was always happy to demonstrate them. He explained that string figures are known world-wide, and the cat’s cradle is actually a series of figures made with a loop of string between two people passing the string forming different images.

Daniel was well-known as a superb cook. In addition to the sourdough starter he nurtured for decades, he was famous for cooking turkeys in a Weber kettle barbeque, and made a mean pot of beans. He was part of the Chia Café Collective, along with his sister Cadie and others such as Lorene Sisquoc and the late Barbara Drake, who cooked many tasty meals that featured Native American foods. Daniel McCarthy and friends provided the feast at the Learning Center’s annual Dragonfly Gala from 2012 to 2018.

Preparing dinner for several hundred people at Dorothy Ramon Learning Center’s annual Dragonfly Gala: a mix of native-plant dishes such as yucca blossoms and purslane, with roast turkey, prickly pear fruit punch, and more.

Ernest Siva had to pull Daniel McCarthy from the Dragonfly Gala kitchen to give him Dorothy Ramon Learning Center’s Dragonfly Award in 2013 for his soaring achievements in saving and sharing Native American cultures(Carlos Puma Photo).

We extend our condolences to Daniel’s family, and to all of his friends who will miss his gentle ways of teaching, appreciation of tribal resources, and love of sharing a good meal. Safe travels, Daniel!

D McCarthy

By Hannah Nyala

Daniel McCarthy (Hannah Nyala Photo)

Early summer, 1986

Cottonwood Visitor Center, Joshua Tree National Monument

The stack of old cards on the ranger’s desk was easy to find, even in the dull light before dawn. I came every three days for a new card, this one no different except earlier than usual, to outflank the coming heat. Flicking on my headlamp — to avoid the building lights, which reliably drew tourist attention and questions — I transcribed the card’s descriptive information into my fieldnotes and hurried out, headed south/southeast. On foot. Alone. On purpose.

That stack of cards held site records done by a young archaeologist, a D. McCarthy, almost 20 years earlier, when I was still enduring middle school, and the sites were in dire need of condition assessments: locate a recorded site, log any changes since the initial record, carry on to the next. Perfect for an archaeologist or, failing that, trained volunteers — neither of which we currently had.

The Chief Ranger, however, knowing my back story — since my children had been abducted a year before, I could be counted on for any volunteer task in the backcountry, so he kept coming up with things for me to do — wouldn’t take no for an answer. “You picked up tracking fast enough. You’ll do fine.”

This, however, I tried to explain, wasn’t tracking, which I had done in some form or another since childhood on the farm, so learning to follow lost people was just another level of a fundamental skill. Condition assessments? Nowhere near my bailiwick. For starters, I had zero archaeology training. More pertinent, perhaps, I was born superstitious and wary of exactly everything connected to the dead or departed and their possessions. But no. Joshua Tree — Cottonwood especially — needed help: these re-assessments were long overdue, the District Ranger had his hands full and couldn’t do it all, our two other volunteers were seasonal and overworked, too. So it fell to me to help out.

For one of the more complex sites that spring, we’d gone out with a group of rangers from topside, and they all had a high old time — joking and laughing all day —sussing out from the detailed notes where the site should be and was, then peering into the crevices, touching the petroglyphs, the pottery shards, the bedrock mortar, kicking back for lunch, talking shop. I eased around paying attention, taking notes, listening, yes, but longing for silence. Grief has a palpable presence, and other people heighten your awareness of it, but I could not walk away from them or myself.

So I went quiet inside, as ever, and set in to wondering about this D. McCarthy. When transcribing the record for my notes, I had never added the name. I knew it—everyone did—but all I had to go on was the work, the diligent attention paid to tiny, crucial points, the evidence of hundreds of hours on foot so far from, well, everywhere. While they laughed and visited, I mulled: Who was this D. McCarthy?

How could someone come to the middle of practically nowhere, find artifacts and places so meaningful to Native people from so long before all of us, and then make a record careful and detailed enough that a bunch of neophytes could walk out, find that site, and swiftly see what had changed since the first record? How on earth can someone do that? I thought this over and over and over again after that first outing, and never came close to a good answer.

On this mid-summer day, however, in a set of nondescript hills that were only tangentially connected to the more well-traveled trails that led toward the oasis, I located the site — exactly where and as described, with its partially buried olla and few pot shards — just as the sun topped the mountains and washed warm over me, and my personal grief stood aside for a few minutes as I crouched there a couple safe feet away, staring at the clay-fired vessel, belonging already to the sand and the times before and after both the ones who made and put it here and this D. McCarthy and now me and my children, still gone, and I understood, not for the first time but for good, this one truth: once you give of yourself, you cannot take it back.

So give your all, all the time, and let the future sort its own self out.

And I opened my fieldnotes and scribbled D. McCarthy in the margin and, for every site I took on afterward, I transcribed not just the details before heading out, but the name. It was congenial, like having a friend in my solitude.

It would be 24 years in the future — and hundreds of miles of solo desert tracking — before I would cross paths with Daniel McCarthy in person and burst out, with way too much enthusiasm for any adult at a professional conference: You are D. McCarthy?!

He grinned, with a bright, mischievous twinkle in his eyes, invited me to sit at his table for lunch, and it was like the sun washing over me that dusty summer day on the hills below Cottonwood. In an instant, he became my mentor on the multi-tribal ethnographic project I had undertaken by then; my strongest supporter; a wise counselor when the project was abruptly stopped, restarted, and then stopped again; a brilliant researcher who could help me make sense of the nuances I was finding in fieldwork but nowhere in the scholarly record; a fellow questioner who helped hone my questions and never settled for a lazy answer; a true friend undeterred by political thickets or anything else. He and Carolyn and Cadie welcomed me to Pinyon when grief came again close to hand, made me feel at home once more in the whole world, demonstrated firsthand how friendship underlies breathing.

Daniel McCarthy. “He was kind to me,” I have heard said over and over again this week, and oh, how I ache, knowing the truth of that simple sentence for so many of us now. I’m all out of words myself, none seem to suffice, and condition assessments are reserved these days for the well-trained, so I simply take my pack, too much water, and a hat, and tramp around the desert, stopping every so often to close my eyes and soak in the light. I swear sometimes I can feel D. McCarthy’s genial grin, and I know the twinkle in his eyes has joined the sunlight for good.

I’m a better person for having felt that, for having known him. We all are.

Walk on, my dear friend, walk on. We’re on your trail.

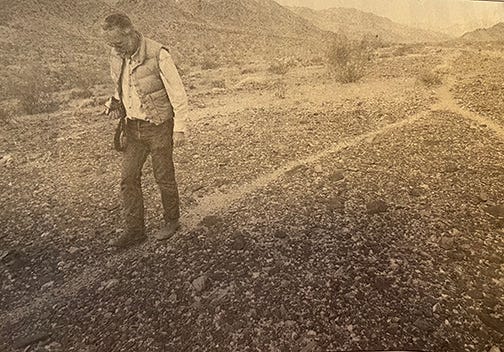

“Amid the Chuckwalla Mountains, U.S. Forest Service archaeologist Daniel McCarthy walks on an Indian trail more than 1,000 years old. Carrie Rosema/The Press-Enterprise.” Published Oct. 10, 1999

Thank you!

Pat Murkland, Editor. February 10, 2021. Contribute to News from Dorothy Ramon Learning Center. Share ideas: EMAIL. Dorothy Ramon Learning Center is a 501(c)3 nonprofit that saves and shares Southern California Native American cultures, languages, history, and traditional arts. Join us at dorothyramon.org and Dorothy Ramon Learning Center on Facebook.