Native Plant Challenge!

We’re springing into spring. To celebrate Earth Day this month, tell us about your favorite native plant or tree. Share your art, photos, poems, brief stories (100 words or so) with us all here, in News from Dorothy Ramon Learning Center. Children’s shares especially welcome. Email your #Nativeplantchallenge story or artwork here:

Ernest Siva:

A favorite plant story

Elder Ernest Siva (Cahuilla-Serrano), president of Dorothy Ramon Learning Center, shares a favorite memory about the native plant creosote for our #nativeplantchallenge.

Kupash (Cahuilla),

Kupat (Serrano),

Barrel Cactus

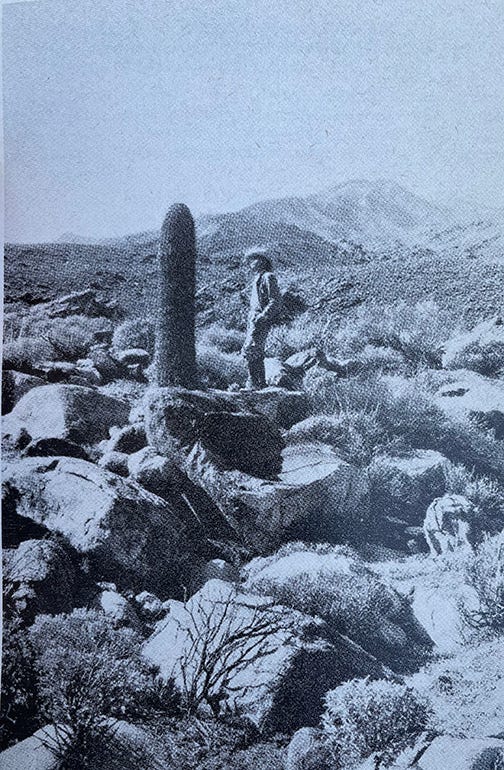

A barrel cactus grows in the Colorado Desert near Palm Springs (Pat Murkland Photo).

By Pat Murkland

The barrel cactus is a treasured resident of Cahuilla desert homelands. Armored with no-nonsense spikes, this portly plant’s Latin genus name, Ferocactus, means “fierce cactus.” No kidding. A fleshy, water-holding plant has to build its own fort of ridges and thorns to defend itself against the desert sun, and those who would eat such plants. Old barrel cacti define what it is to be a survivor; they seem to grow as tall as the saguaro in Arizona’s neighboring Sonoran desert. Fortunately I never backed into any barrel cacti (and I’m not telling that other story).

The barrel cactus is a friend, not a foe, of Native American people — a resource of both food and water. The Serrano word for “drinking,” paa', embedded in the cactus name, kupat, tells a story of how certain species of barrel cacti gave emergency water to desert travelers. (Note: Not something to try; drinking from cacti can easily poison you.)

Before flowering, the emerging young buds (kupachem in Cahuilla) offer a nutritious springtime food, which the late Katherine Siva Saubel sought for her traditional Cahuilla dish.1 In the 1990s she had to travel high into the Santa Rosa Mountains to gather the young buds because the barrel cacti, once plentiful near the desert mouths of canyons and traditional village sites,2 have been decimated since newcomers began arriving in the 1800s in Southern California’s First Nations.

To avoid those sharp, thorny defenses, Katherine Saubel thanked the plant in Cahuilla, and then picked buds with special wooden tongs, always leaving some buds behind so the cacti could continue to thrive there. Once home, she parboiled the buds to get rid of the alkaloid bitterness, just as her mother did. “Pé'iy áchakwe' mewáxniqa', She would dry them thoroughly,” Katherine Saubel said in her 2004 memoir. “Pén háni' 'áy mewénqa' ku pé'. … Pén 'áy máwa' 'áy támiva' 'áy pé'iy pánga' pé' pechúpinqa'. … Pé' michemqwáwe' pé'emi'. And then she would store them away. … And then later in the winter she would soak them in water. … And we would eat them.”3

Harvested barrel cactus buds boil in a photo with an article by Alice Kotzen about Malki Museum’s third agave roast, in the Malki Matters newsletter, Spring 1997, page 3.

Katherine Saubel canned her barrel cactus buds. And that’s how I had the opportunity in the 1990s to first taste and eat this marvelous and delicious traditional dish, part of the original California cuisine. A true lifetime experience.

When the buds bloom, the barrel cactus contradicts its own fierceness and wears a beautiful crown of flowers. I will never forget the first one I saw blooming so vividly in the wild. They are now so rare.

What’s your native plant story? Click and tell us here: #nativeplantchallenge.

The Story of the Devil’s Garden

A 1930s postcard printed in Los Angeles showcases barrel cactus “on the desert” near Palm Springs. (Courtesy of Pat Murkland)

In traditional Cahuilla homelands east of Whitewater Canyon in what is now Riverside County, a desert plain once contained “a wider variety of cactus species than perhaps any other equivalent area of this size in the American southwest.”4 Much of this was barrel cactus, a primary food source to the Wanakik Cahuilla.5 Imagine a sea of blooming barrel cacti every spring.

The grumpy December 1823 diary of José Mariá Estudillo complained about the Romero-Estudillo expedition’s struggle across this plain, “sandy and rocky country, the land covered with gobernadora [chaparral] , choyas [teddy-bear cholla], funeras [Mojave yucca], biznaga [barrel cactus], mesquite, mesquitillos and others, and without pasture for the animals.” 6

Later immigrants loved the cacti more — so much that they began taking the plants. In 1894, landscape architect Franz Hosp removed many cacti that were planted as popular attractions in what became the Southern California city of Riverside’s White Park. 7

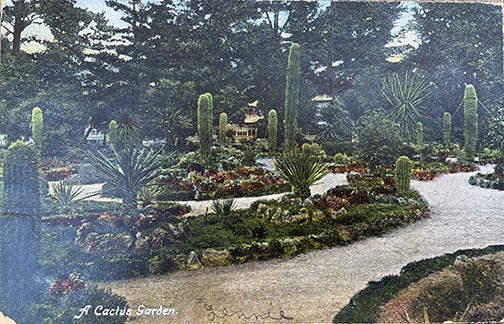

This penny postcard printed in Los Angeles circa 1907-1909 shows barrel cacti and other cacti in White Park, which was originally named City Park, in Riverside, CA. The cacti were taken from the “Devil’s Garden,” Cahuilla homelands east of Whitewater Canyon. (Courtesy of Pat Murkland)

The Devil’s Garden near Whitewater Canyon became a popular sightseeing spot. Naturalist writer J. Smeaton Chase in 1923 directed Palm Springs tourists by “cross-country horseback” or automobile (“there are two bad sandy stretches of the road,” he warned those 1920s drivers) to “The Devil’s Garden … a natural cactus garden, where many species of cacti are associated in what amounts to a thicket of these odd vegetable forms.”8

A photo from J. Smeaton Chase’s 1923 book, Our Araby: Palm Springs and the Garden of the Sun, promotes the barrel cactus as a tourist attraction, “a strange inhabitant of the Garden of the Sun.”

By the mid-1920s, cactus home gardens had became popular, and many, many more cacti were removed and sold in Los Angeles and other places.

A postcard of a cactus garden dominated by barrel cacti, printed in Los Angeles and dated 1908, was sent from Long Beach to a young woman in Kansas who probably hadn’t ever seen such plants. (Courtesy of Pat Murkland)

Then, they were gone. Today, the plentiful cacti of the “Devil’s Garden” are but a memory, and the land is covered instead with wind turbines. We hope that somewhere amid the streets of LA, those cacti descendants still grow.

Join the Native Plant Challenge!

Celebrate native plants. Celebrate Native cultures and nurture our community wellness and health. We value your contributions: EMAIL. Thank you! Dorothy Ramon Learning Center, a 501(c)3 nonprofit, supports our community working together to save and share Southern California’s Native American cultures, languages, history, and traditional arts. Subscribe to News from Dorothy Ramon Learning Center. Join us at dorothyramon.org and Dorothy Ramon Learning Center on Facebook. Pat Murkland, Editor. April 7, 2021.

Kotzen, Alice, Malki Museum’s Native Food-Tasting Experiences, third edition, 1996, Malki Museum, p. 17.

Bean, Lowell John, and Katherine Siva Saubel, 1972, Temalpakh: Cahuilla Indian knowledge and usage of plants, Malki-Ballena Press, pp. 67-68.

Saubel, Katherine Siva and Eric Elliott, 'Isill Heqwas Wáxish: A Dried Coyote’s Tail, Malki Museum Press, 2004, Book 2, pp. 884-887, “Problems with Windmills.”

Bean, Lowell John, Sylvia Brakke Vane, and Jackson Young, with contributions by Bern Schwenn. The Cahuilla Landscape: The Santa Rosa and San Jacinto Mountains. 1991, Ballena Press, p. 47.

Ibid, p. 11.

Bean, Lowell John, and William Marvin Mason, The Romero Expeditions, 1823-1826. 1962, published by the Ward Ritchie Press for Palm Springs Desert Museum, pg. 36 and pg. 101.

Gunther, Jane Davies, Riverside County, California, Place Names: Their Origins and Their Stories, 1984, © Jane Davies Gunther, Rubidoux Printing Co., p. 155, “Devil’s Garden.”

Chase, J. Smeaton, Our Araby: Palm Springs and the Garden of the Sun, 1923, republished 1987 by the City of Palm Springs, p. 41.